As health systems are adapting to increased accountability for quality outcomes, population health, and collaborative care, medical schools are adapting curricula to better prepare physicians to function in health systems. Two components of this educational transformation are (1) increasing physician competence in Health Systems Science, including quality, population health, social determinants of health, and interprofessional collaboration, and (2) providing roles for students to act as change agents while adding value to the health system. The authors, three medical students who served as patient navigators during their first year of medical school, provide perspectives regarding their clinical systems learning roles, which spanned the levels of individual patients, clinic operations, and the health system. Specifically, authors describe working with a struggling patient, developing an intake assessment tool to aid clinical operations, and creating a directory of community-based resources. Authors discuss educational benefits, including understanding social determinants of health, barriers to care, and inefficiencies within the healthcare system. Several challenges are explored, including the importance of student initiative and concerns about traditional curricular outcomes. Through early experiences, students describe developing a professional identity as a change agent, while also learning key competencies required for clinical practice.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Healthcare is rapidly transforming to focus on improving patient experience and population health, reducing costs, and preventing provider burnout. 1 To adapt to these changes, US medical schools are transforming curricula to better prepare systems-ready physicians who can function in interprofessional teams and contribute to healthcare change. 2,3 Recently, there has been increased emphasis on Health Systems Science (HSS) education, which includes concepts such as population health, social determinants of health, high-value care, and collaboration. 4,5 In this context, schools are piloting experiential roles for students such as health coaches, patient navigators, and systems analysts, so students can learn HSS competencies while potentially adding value to health systems. 6,7,8,9,10,11,12 However, implementation of new experiences involve challenges, including student engagement and buy-in from faculty. 13 Medical students are key stakeholders in educational transformation, and their perspectives regarding these changes have not been reported. 13 As students who participated in such roles, we have a unique perspective on these new curricula. In this article, we describe how our experiences as patient navigators allowed us to serve as change agents at the levels of patient care, clinic operations, and the health system.

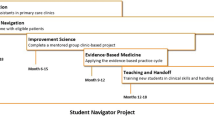

Prior to 2014, Penn State College of Medicine students were not significantly integrated into clinical sites until third-year clerkships; in 2014, all first-year students were enrolled in a required 9-month HSS curriculum, which included a patient navigator role that embedded students into clinical sites. 7,14 Patient navigation is an intervention using outreach workers to assess barriers to care and assist patients in navigating complex healthcare systems to optimize care and reduce disparities. 15 In 2015–2016, pairs of students were placed across 36 clinical locations, spending two afternoons per month at their site. Each pair was assigned a faculty mentor, varying between nurse practitioners, care coordinators, and physicians. Students worked with their mentor and clinical staff to identify and address patients’ barriers to care.

Each assigned to a different clinical site, we describe three case studies that highlight our experiences and perceived change contributed at the levels of the patients, clinic operations, and health system.

One of us (K.S.) was placed at an outpatient Internal Medicine clinic under the mentorship of a nurse practitioner and care manager. With mentorship, a classmate and I used the electronic health record to identify patients who missed multiple appointments. Through phone calls and face-to-face visits, we identified patients with financial and/or psychosocial barriers who might benefit from assistance. We called several patients, ultimately focusing on the care of three, whom we called several times a month, followed up on medical adherence and medical equipment and transportation access, accompanied to multiple doctor appointments and visited at home 2–3 times throughout the year.

Upon visiting the home of “Mary,” an 84-year old with multiple comorbidities, including Parkinson’s disease, osteoporosis, and myofascial pain syndrome, we were overwhelmed by the complexity of her situation. We learned her primary means for transportation was her ex-husband, who she described as unreliable and with an alcohol abuse disorder. This context provided us with a better understanding of her “no-show” record. In her cluttered apartment, Mary had fallen three times the past year, resulting in two fractures. After performing several home visits, it became clear the type of assistance Mary required: a motorized wheelchair and in-home ramp, a walk-in shower, and a dependable source of transportation. We became Mary’s “liaison” and helped her apply for public assistance. We also advocated for Mary while she was in clinic and, following visits, educated her and clarified confusing areas of the care plan.

Perhaps the most significant barrier Mary faced was her need for homecare. Although she qualified for state assistance, the approval process proved to be lengthy. Meanwhile, we looked for ways to find her help at home. Without immediate resources, we reached out to local churches and found an organization excited to volunteer weekly to help Mary with activities of daily living. In conversations, we also learned about the pride Mary took in jewelry making, an activity she had largely given up secondary to her Parkinson’s disease. Church volunteers were happy to assist her with beading so she could continue her passion. With each intervention, Mary regained autonomy. Though the course ended before we could observe the effect of these efforts on Mary’s health, we learned from our student successors that Mary had increased independence and no recurrent falls.

While this experience elucidated practical ways in which we could contribute to patient care, we recognized this largely depended on working with a committed mentor who understood our potential. Students whose mentors did not match their enthusiasm or struggled to assist them in identifying appropriate patients did not feel they gained the same value from the experience.

One of us (C.S.) and a partner were placed in a Pain Management Clinic, which did not have a designated patient navigator or coordinator. We initially found ourselves shadowing rather than working directly with patients and addressing their needs. This experience was not unique, and in fact, several classmates expressed concern regarding autonomy. With time and through multiple meetings with the course coordinator, however, we gained confidence and found support from both faculty and our site mentor who encouraged us to become “change agents.” Through our initial observations, we learned the clinic’s process of communicating with patients and identified gaps in addressing patient barriers. Most notably, we identified the lack of standardized methods for identifying roadblocks within patient care plans. Many patients missed appointments, experienced discrepancies in medication refills, and were affected by failure of coordination between providers.

We developed a patient questionnaire and administered it during visits to proactively identify barriers. The questionnaire asked about transportation to/from appointments, financial concerns, and difficulty understanding information received from care teams. These questions were derived from what we observed and heard patients express while we shadowed in clinic and material learned during our HSS course. Administering the questionnaire allowed us to spend one-on-one time with patients to elucidate barriers and then communicate their case to the care team. After visits, we followed up with patients to ensure that their challenges were addressed. In short, we were able to contribute a novel patient-centered tool to this clinical site that is now integrated into each student patient navigator consultation.

Throughout the program, we were surprised by the complexity of the problems our patients endured. Intricacies of our patients’ situations made it difficult to know where to begin to help them. To address our frustration and foster collaboration, our HSS course provided several opportunities for students to share challenging cases and brainstorm solutions. One of us (C.M.), along with a team of interested students, realized how critical addressing these issues was to meeting patient health goals. Our desire to help patients, however, was impeded by the fact that resources and interventions for patient needs were either challenging to identify or non-existent. After talking with site mentors, it was clear many of them also struggled with the lack of transparency regarding community-based resources.

Upon gathering resources from each student’s site, we quickly realized the plethora of information available in the community and health system. Unfortunately, resources were often siloed, site specific, or out-of-date. Some clinics worked exclusively with certain agencies and overlooked potentially more cost-effective or geographically closer options. Most resource guides were “homegrown,” existed in over-filled binders, and were either inaccessible or not user-friendly. We were also struck by how quickly resource directories were “out-of-date.” In small-group discussions with peers and faculty, we recognized the extent to which system-level problems impact individual patients. Despite frustration and even disillusionment, we were encouraged to pursue innovative solutions. We systematically solicited input from classmates, mentors, and area agencies regarding effective resources. We developed a “Health System Resource Guide” in an online searchable website. This website contained resources across four counties, including information on meal, housing, and childcare assistance, how to apply for waiver and federal assistance programs, and programs for medication assistance. A key feature of the website was that it could be edited and maintained by subsequent students. Collating previously scattered resources into one location provided a means for students and providers to efficiently browse and identify resources that can facilitate improved outcomes.

We have come to understand that for the program to be successful, buy-in is required on many levels. In our narratives, we describe instances in which mentors understood and fostered our potential, anecdotes of taking initiative to improve the experience, and examples of the palpable agency students can demonstrate in clinical sites. While our experience in patient navigation was positive, not all of our classmates shared the same perspective. Students who exhibited less interest or engagement did not glean the same value. We witnessed several invested students who were matched with faculty and team members who did not fully recognize the potential of student patient navigators, which impaired student confidence and initiative. Ultimately, regardless of the mentorship or support provided to students, students must take their own initiative and have ownership of their role. This was especially evident in situations where students had the same opportunities at the same site but varied widely in engaging with colleagues and patients. We also learned that many of our classmates, including ourselves at times, struggled to balance engagement in the program with the magnitude of work required to perform well on examinations in other parts of the curriculum. 16,17,18 As such, we observed students grappling with how to balance this tension, and the doubts and dissatisfaction that ensued. With buy-in and understanding from students, faculty, and mentors alike, students have potential to make a lasting impact.

While we assumed we would not contribute to patient care until our clinical rotations or possibly graduation, this experience proved otherwise. The patient navigator roles complemented our HSS course and demonstrated how we can meaningfully help patients prior to acquiring traditional doctoring skills. Working within healthcare teams, we provided services ranging from helping patients with individual barriers to tackling systems-level concerns. Our roles as student patient navigators complemented care provided by other team members and permitted us to learn about their roles. As students, we are in the unique position of having time to spend with patients, perform legitimate tasks, and add a voice of advocacy for patients most in need. Through these patient-centered experiences, we more fully recognize our lifelong journey of contemplating ways to improve the system we are entering and our professional role to do so. 19

In a time when the US healthcare system is characterized by patient outcomes that are incongruent with healthcare expenditures, we are experiencing a program that allows us to learn HSS. 20 We are learning the sobering complexities of care delivery, and ways in which patients are vulnerable to poor outcomes. The skills of identifying and addressing barriers at both the patient and system levels are crucial to our development as systems-minded physicians who actively question processes and inadequacies, and strive to change the system. As aspiring physicians, we recognize the importance of understanding the complexities of the healthcare system and learning to work effectively within it. We hypothesize the combination of early opportunities to meaningfully connect with patients concurrent with mentored opportunities to employ critical and systems thinking empowers us to act as change agents.

From our experiences in the first year of medical school as student patient navigators, we believe students can add value to patient care, clinic operations, and health systems. These roles have the potential to enhance education in social determinants of health, population health, and healthcare systems, while increasing recognition of a professional role identity as a “change agent.” Current emphasis on examinations and residency outcomes and variable faculty buy-in are, in our view, important impediments to student engagement and development as systems-minded, patient-centered physicians. We believe our experiences support ongoing efforts to more broadly support and prioritize these initiatives in medical education.

The Systems Navigation Curriculum at the Penn State College of Medicine was developed with the financial support from the American Medical Association (AMA) as part of the Accelerating Change in Medical Education Initiative. This work was also partly funded by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.